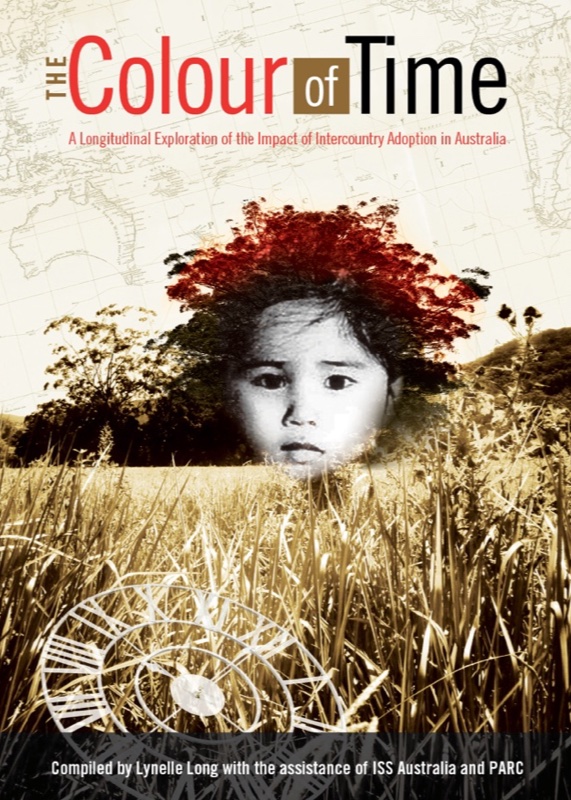

I would like to begin with The Colour of Time, the recently published book which provides 28 intercountry and transracial adoptees the opportunity to reflect, as adults, on being adopted. You played a significant role in compiling this book, including contributing your own story.

The book is a sequel to The Colour of Difference which was published over a decade ago to which you were also a contributor.

Both books have wonderful titles. Who came up the titles and why are they so fitting for stories about intercountry and transracial adoption?

I came up with the title and the book was my brainchild. I knew there was very little that looks longitudinally over time on how we, as intercountry adoptees, journey past adolescence – past the time when we leave the nest of our adoptive family homes and become totally independent; to think for ourselves, create our own lives outside their influence, and to show how adoption is a life journey.

To tie the two books together, ‘time’ as a concept became the focus of the sequel to follow up on the original contributors after 16 years.

A further parallel concept of ‘time’, was including the newer, younger generation – something suggested by the Federal Government – to see what differences, parallels and/or similarities existed in how these adoptees are experiencing their life journeys.

The ultimate question not overtly asked, but which hopefully the book addresses to some degree, is whether the mandatory education which adoptive families now receive for intercountry adoption has helped in any way to smooth the path for the adoptees. My impression on knowing all the stories intimately is, “absolutely yes!” The younger adoptees seem to be raised with more openness and awareness of the need for embracing their culture and origins rather than the blind parenting concept which adoptees of my generation had of “love them as your own and everything will be fine”.

Having being involved in both publications, which collectively cover 55 personal stories, what changes have you seen in yourself and in others as a consequence of sharing your experiences with a wider audience?

For myself, sharing my story has helped create some meaning to my life, to my adoption. I shared with the intention of using my experience as a learning tool to enable improvements in the experiences of younger adoptees as they are growing up. Reducing their sense of isolation and to ‘normalize’ their experiences so they don’t grow up feeling like a freak or some abnormality like I did during my early years.

The changes in myself between the two books has been massive! Just prior to writing in The Colour of Difference I was suicidal, severely depressed, had no self-esteem, ashamed of my physicality, due to my Asian-ness, and didn’t recognize I had any ‘adoption related issues’. I could go on with the list of symptoms.

Today, I am married to an Aussie Asian and I feel pride about being Vietnamese. I am happy and feel my life is balanced. I am able to express my feelings and experiences without being triggered back into that emotional space which was unstable and not very positive. I’m able to reach out and give peer support to others who are journeying a similar path.

I believe the power of sharing who we are and having our experiences validated is hugely important in our ability to heal. It allows us to integrate the many aspects of ourselves that get denied in being adopted.

For others and myself involved in the two books, I’ve seen, over time, a coming to terms with the traumas, the pains, the grief, reconciling the multiple facets and complexities involved in our adopted lives and an acceptance of ‘what is’ based on acknowledgement of, and sometimes a complete immersion in ‘what was’.

Your involvement with intercountry and transracial adoptees is a long one. Next year will mark the twentieth anniversary since you began the Intercountry Adoption Support Network (ICASN) in Sydney. This organisation is still going strong, changing its name to Intercountry Adoptee Voices (ICAV) a couple of years ago. Congratulations on this pending milestone. If we go back to the late 90s what prompted you to establish ICASN?

I began ICASN out of the powerful healing I received in being able to meet and connect to others for the first time, who shared a similar journey.

I no longer felt alone. I wanted to replicate that and make it possible for other adoptees like me to feel the same.

How have you managed personally to sustain two decades of helping other intercountry and transracial adoptees and advocating for their rights?

I did take a break at one point for two years when my own children were young and I needed to focus on being a parent and giving to my own family. Having that break when you need it is important.

Over the years, I’ve learnt the value of giving to myself and looking after my own mental health first because otherwise I’m no good to anybody.

I think the hardest part of working with other adoptees is that we inadvertently can trigger one another’s vulnerabilities – for example, I could count the numerous times I’ve felt overly sensitive to ‘rejection’ from other adoptees.

Our adoptive vulnerabilities never leave us and for me, I’ve learnt how to listen to my body and what it tells me so that I can manage my emotions, soothe myself and do my best to not ‘react’ back.

I’ve gained much from my work in this area – personally I’ve made some amazing life-long friends, as I mentioned earlier it has also created an additional layer of meaning to my adoption and why I’m here on this earth, and I just love seeing the growth in other adoptees as they navigate their maze.

I’ve gotten a real buzz from seeing the new services become available to intercountry adoptees as a result of all these long years of hard work, speaking out and being a passionate advocate – it has really helped me to feel that it has been worth the effort despite the down times.

A concept my therapist helped me understand in my mid-20s has held me in good stead all these years: she said I must be a lot like my mother (meaning biological mother) because of my resilience and strength in all that I had endured. Once I learnt to connect to my mother who is intrinsically a part of me, inseparable in spirit even though we are physically separated, I’ve been able to overcome my adversities and flourish.

You have been an active representative on many committees and forums for intercountry and transracial adoptees. How have services changed in the past twenty years and what are the critical support structures still needed?

The change in Australian intercountry adoption services has seen a shift from mainly pre-adoption and meeting the needs of the adoptive/prospective parents to recognizing the importance of post-adoption support and the adoptee becoming more in focus.

It is the recognition that adoption is a life long journey, rather than a once off transaction completed when the adoptee joins the adoptive family. This shift is long overdue but is still lacking in the following critical support structures:

- the underlying philosophy of adoption needs to change to ensure adoptees are allowed to keep their original birth certificates intact with full details of their birth parents and to list adoptive parents as adoptive parents, not ‘as if born to’ parents.

- the importance and recognition of adult intercountry adoptee organisations to provide peer support and services, via the provision of funding by the governments who agree to and facilitate our adoptions.

- legal, financial, translation and emotional support for those adoptees who were trafficked, stolen, or lost but adopted via intercountry adoption processes, who wish to find their biological families, or who have found them but need ongoing reparative justice services to enable them to move forward with their lives.

- recognition by providing adequately funded and trained services that not all adoptions work out well, some adoptees are re-homed or placed as State Wards or other types of care within the adoptive country. This just adds another layer of trauma and for an adoptee to ever move forward, they need the right support to help them process and deal with these multiple traumas.

- ongoing deep mental health services and support specifically trained in intercountry adoption.

- DNA testing upon relinquishment prior to intercountry adoption with the data kept on both the child and the relinquishing person – ensuring a biological connection between the child and adult relinquishing, and later assisting with reunion or ongoing contact.

- currently there is no international body or process for placing criminal charges for those whose adoptions are illegal or suspect. The Hague Convention in ICA and the UNCRC are both toothless tigers and offer nothing to protect the adoptee when their rights are violated and interests clearly not met. Currently, intercountry adoptees have NO rights and this needs to change if intercountry adoption is to ever be considered an ethical practice.

- the other important point to note is while services in Australia have changed for the better, our sending countries still need to recognize adoption as a lifelong journey. Many (with the exception of South Korea) have not developed post adoption services for adult adoptees wanting to return, search, reunite, or learn about their origins.

- lastly, the final frontier in intercountry adoption is that it is dominated largely by adoptive families, the adoptees and professionals – we are yet to hear from, and include, our biological families. Their voices are squashed in our sending countries, they have less rights than us adoptees, their voices are unrecognized and not even sought. Their whole journey of loss and grief is totally unsupported. I hope I live to see the day our birth families are recognized equally and their experiences impact greatly on how intercountry adoption is considered and conducted.

In learning from the experiences of fellow intercountry adoptees who find their biological families, the decision to give up children seems largely from a lack of resources and choices due to poverty or war, attitudes toward and treatment of women, and the greater politics within their country. For those whose children are taken by force or gotten lost, it seems little value is given to family reunification because the monetary incentive for supplying children is too great. If biological parents could ever be fully supported to keep or be reunited with their children and be granted rights above those of adoptive parents to keep their children, there may no longer be a need for intercountry adoption.

I agree Lynelle that if our mothers and families were supported at their time of greatest need original families could stay together and there would be no need for adoption.

The additional support services you raise show how complex and far reaching the impacts of adoption are. It also leads me to ask the following. Adoptees, whether their origins lie in domestic or intercountry arrangements, are often marginalised, their needs sidelined or misunderstood. Living with your own adoption and having borne witness to many other adoptees life stories what aspects of adoption do non-adopted people have great difficulty grasping when it comes to understanding what its like to lose a mother, family, country and heritage?

When people know I am an intercountry adoptee, the most often repeated phrase I always get is “you are so lucky” or “what amazing parents (meaning adoptive) you have”. People always see only the glossy side of intercountry adoption, for example, referring to the material gains where we typically move from a poorer non-white country to a wealthy white country. What they fail to grasp are the multiple losses that are emotional and spiritual — loss of identity and knowing basic facts about ourselves, loss of kin and the absence of not being able to have that all important reflection back of oneself from biological family.

You were born in the 70s during the Vietnam War and adopted into Australia at five months of age. You grew up in rural Australia with an adoptive family that catered for your physical needs but struggled to understand the extent of your primal loss and the challenge of having to fit in, as one of the few Asians in your new local community.

You have written that you experienced deep loneliness and sadness in your younger days as a consequence. In your early twenties your life unravelled into depression with suicidal tendencies. What helped you through these difficult times?

I’m not sure exactly – possibly supportive people like the therapists in my life at the time but unfortunately I didn’t turn to them or other people when I was suicidal and I did attempt quite a few times.

The depression and pain was so intense I just wanted everything to go away.

I felt so alone and I felt like no one cared. I’d lived a life of harsh reality and I couldn’t pretend to be okay anymore.

I know when I attempted the last time and I ended up in emergency, the medical staff were so cold – they saw attempts like me all the time and I got the gist that I was a waste of their time when it could be spent on someone else fighting to live. To them I was just another one that they felt obligated to work on!

Lying alone in hospital afterwards and being given a taxi home because I had no one who knew or gave a damn … I was at my most alone point ever!

Something inside of me asked whether I was going to let those damn perpetrators win. I had a survival instinct which I say most likely comes from my mother. I wasn’t going to let my life continue to be such a s**t hole.

I wanted it to be better.

I guess you can say being at such a low point numerous times, I finally had the motivation to make it better because I just couldn’t cope with it being like that for too much longer. I knew at the end of the day, only I could get myself out of my hole. So perhaps it was sheer willpower to make my life worth something.

It also shows personal courage, a depth of inner strength we often don’t know is there until we reach the darkest depths.

For more than four decades you knew little of your personal information until you engaged a private investigator, in Vietnam, to search on your behalf. What was he able to find and what impact did this have on your life?

He found my birth certificate which confirmed my original name, date of birth, place of birth, time of birth, and my mother’s name, and a witness name.

One year later I sat in limbo wondering whether I really wanted to search for my mother and find her.

The private detective found five women in South Vietnam with her name but he mistakenly didn’t accept any of them because he assumed from my original surname that I must have Chinese ancestry and all these women were of Vietnamese ancestry.

Since then, I’ve done two DNA tests which show I’m completely South East Asian. So now I realise one of those five just might have been my mother. I feel for those women who had a momentary glimmer of hope or perhaps a re-opening of their trauma of loss.

I’m very aware of these realities as I’ve put together the paper on Search and Reunion: Impacts and Outcomes of over 43 intercountry adoptees who have searched and reunited.

I’ve also reviewed the book about the South Korean birth mothers and met many mothers in Australia who lost their children to adoption. I’m perhaps too aware of the realities and now I feel afraid to open pandora’s box.

With intercountry adoption, reunion is so complicated because I’ve been raised in a completely different culture with different language, values, ways of seeing life compared to my mother and extended family.

Ultimately, I ask myself what do I hope to achieve if I search for her because I think it’s self centred to search only to find out basics – what about her feelings and needs? I’m aware she has probably experienced as much trauma, if not more, than me.

I’m also aware that reunion means opening up a whole new realm of complexities and traumas. Do I really want or need that in my life when I’ve finally reached a peaceful calm about who I am?

So, here I sit pondering. I am booked to travel to Vietnam in February 2018. Perhaps I’ll feel differently when back in my home country.

These are important factors that need to be considered Lynelle. Like most things with adoption there are seldom easy or straightforward answers.

Returning to your search you did obtain some key personal information, including your original name, Ung Thanh, that was given to you by your mother. Finding documentation with your original name must have been special. Can you describe the feeling and what it meant to you?

Actually I was just in shock because the person who contacted to advise me was not somebody I knew who was involved in my search. So I was immediately suspicious until I confirmed she’d been hired by my private investigator.

Then I was just so happy because at last I could confirm what my basic identity and birth details were. I’d never known if the date I had was correct or where it had come from. It was.

I’d never known where I was located because I was not from an orphanage – it turns out I came from the largest maternity hospital in Vietnam.

I’d never known the time of my birth – it turns out I’m a morning person which makes sense as I’m always up at the crack of dawn and go to bed early.

Most importantly, I’d never known my mother’s name and here it was – so similar to mine. Clearly she’d named me after herself – maybe as a means of allowing me to trace her?

You are married to a supportive husband and mother to two biological children. What has motherhood taught you about your adoptive experience and has it brought any shifts to your sense of identity?

Fundamentally, motherhood tells me what I always knew within – that we adoptees NEVER forget our mothers, just as mother’s we never forget our children.

As a mother I am imprinted with the knowledge and sense of my children. I would miss them forever if I lost them.

I would never get over their loss.

Motherhood has deepened my understanding of the loss that my mother has probably experienced. It has brought me closer to understanding intuitively why I have always felt so connected to my own mother and why that yearning to find her is so natural for us adoptees.

Motherhood has added on another layer to my identity because in watching, and actively participating. in my children growing up I’ve gotten to vicariously relive my own childhood and learn how to be proud, twice round, of my Asian genes and heritage. Once, through my own therapy work and visit back to homeland, and second time around, via my children.

I look at them and think how beautiful their little faces and souls are and I can’t help but feel a twinge of sadness that I didn’t grow up like them, feeling much loved, accepted for who they are and surrounded by people who mirror them.

Your reflections on motherhood are a good place to end Lynelle / Ung Thanh. Thank you for the opportunity to chat about adoption and the book The Colour of Time, which I encourage people to source via the ICAV website for a hardcopy or via Amazon for an e-copy.

Your tireless energy in support of intercountry and transracial adoptees is an inspiration and much needed. All the best with the future in your role as mother, partner and supporter of the rights and needs of adopted people. Enjoy your next visit to Vietnam and resolving whether to take any further steps to locate and meet your mother.