This article is a summary of my thesis on adoptees and counselling. The thesis was entitled ‘Adoptees’ Perceptions of Their Counselling Experiences and Suggestions for Counsellors’. It was submitted as part of the requirements of the Masters in Psychology Counselling at Monash University in January 2017.

Adoptees’ Experiences of Counselling

Counsellors are not usually provided with even a basic introduction to adoption in their training, much less an explanation of the complexities involved (Dennis, 2014), and so it is unsurprising that many adopted adults have expressed frustration with their counselling experiences (Kenny, Higgins, Soloff, & Sweid, 2012). Whether through training or self education, counsellors working with adoptees need to consider their own preconceived ideas about adoption (Baden & Wiley, 2007) and understand the rights and emotional losses of each member of the adoption triad: natural parents, adopted persons, and adoptive parents (Silverstein & Kaplan, 1988).

For many adoptees, the effects of the original separation from their natural mothers holds significance (Verrier, 1993; Dennis, 2014), but this is often dismissed due to the difficulties associated with supporting such a position empirically. Despite numerous myths surrounding adoptees (Friedlander, 2003), and confusing discrepancies in the research literature, a client who was adopted must be respected as the experts of their own lived experience, allowed autonomy within the counselling process, and shown understanding and empathy.

Up until the 1980s, adoptees were denied access to their birth records, which meant that they were unable to locate their natural family members, and so remained disconnected from them. Adoption was shrouded in shame and secrecy, with the adopted person expected to be grateful for their adoption (Kenny et al., 2012), and there was little recognition of the need to grieve (Dennis, 2014; Lifton, 1994; Robinson, 2004). Furthermore, Verrier (1993) has identified a lack of understanding of the importance of mother and infant ‘bonding’ (commencing in utero and continuing into the post-partum period), and the subsequent expectation that the infant will form an ‘attachment’ to another primary caregiver who is a stranger to the infant. This forms the basis of the ‘primal wound’ theory, which contends that ‘babies who are separated from their mothers at birth experience her loss as abandonment, which is stored in the baby’s implicit memory’ (p 50). Whilst this theory has been controversial, many adoptees view it as paramount to understanding their issues well into adulthood.

Australia’s adoption history, and the attitudes and ideals that shaped it, helps shed light on the preconceived ideas about adoption that many people hold, including those in the counselling profession. To date, there has been very little research on the immediate effects of counselling for adoptees, although Kenny et al. (2012) of the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) found that many participants expressed frustration with their experience of GPs, counsellors, and other professionals. In contrast, those who had good supports found it ‘lifesaving,’ particularly where there was a proper understanding of adoption-specific issues. Amongst the recommendations of Kenny et al. was the need for adoption to be ‘viewed through a trauma lens’, with mental health professionals trained in adoption-related issues such as trauma, relational interactions, attachment, and abandonment.

Most of the literature on adoption either focuses on the contrast in levels of adjustment between adopted and non-adopted people, or on the disproportionate number of adoptees found in clinical treatment settings, but does not investigate appropriate treatment options. The majority of research on adoption is American, and so the current study contributed to the limited knowledge base relevant to the Australian context. The study also contributed qualitative data that gives a voice to the lived experiences of adopted people, currently lacking in much of the adoption literature.

Method

The study sample comprised 11 adopted adults, 10 female participants and one male, ranging in age from 43 to 68 years, with a mean age of 48 years. Their ages at the time of adoption were between six days and two years. The research question for the study was ‘What perceptions do adopted adults have of their counselling experiences?’ The aim of the study was to explore these perceptions and provide suggestions for counsellors from the adopted person’s point of view.

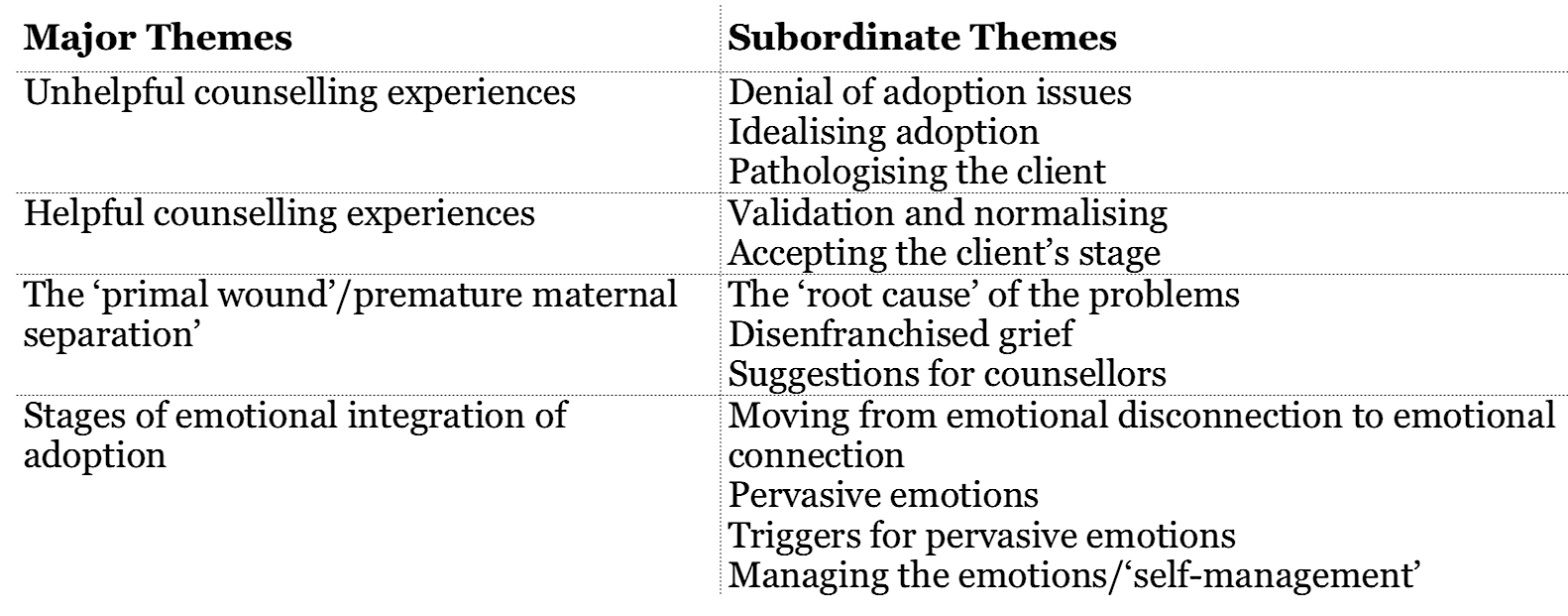

Results were analysed using thematic analysis where themes were derived first for each individual and then across individuals, and then identified at a group level. Nine themes emerged as shown in the table below.

Major Themes and Subordinate Themes

Results and discussion of themes

Almost all the participants were able to find counsellors who proved helpful to them, and yet more than half had first experienced unhelpful counselling. Other themes emerged relating to ‘premature maternal separation’, or Verrier’s theory of the ‘primal wound’. These included the disenfranchised nature of grief resulting from adoption separation, the emotional integration of adoption, and the stages across the lifespan that participants typically went through in coming to terms with adoption.

Unhelpful counselling experiences

Most of the participants felt that the counsellors they considered unhelpful didn’t ‘get it’ and were either unable to put their preconceived notions concerning adoption aside or were unaware of them. As a result, the participants’ experiences with such counsellors were seen as an extension of the stigmatisation and disenfranchisement that had occurred throughout their lives.

The three main themes that emerged from unhelpful counselling experiences relate to the perceived attitudes of the counsellors: denial of the effects of adoption, idealised attitudes towards adoption, and being pathologised without exploration and validation of the distressing aspects of their adoption experience.

Helpful counsellors

The helpful counsellors validated and normalised the adoptees feelings. They also accepted the stage the adopted person was at in terms of their awareness of the impact of their adoption. Some of the adoptees were searching and felt adoption to be immensely important. For others, it didn’t seem important to them at the time they sought counselling, but became important later. The approaches described above included validation, acceptance, empathy, and accurate reflective listening. All of these are covered in any counselling training, and yet, in relation to the unhelpful counsellors, this basic training was not apparent.

Dennis (2014) and Grand (2010) suggest that counsellors who dismiss an adoptee’s own thoughts, feelings, and adoption narrative, despite their training to the contrary, may have been unconsciously influenced by older, outdated attitudes. As Dennis puts it: ‘it takes an active effort on the part of therapists to become aware of their own conscious or unconscious participation in this cultural myth and pierce their collusion in it’ (p. 92).

Without an understanding of the complexities of adoption, or that it differs from the non-adopted experience, counsellors may be unaware that the intensity of distress experienced by adoptees is a normal reaction.

Had the counsellors of the participants used a trauma informed approach, as later recommended by the APS (2015), Green (2014), Kenny et al. (2012), and Kenny et al. (2015), it is more likely that they would have been presented with respectful, in-depth assessments rather than dismissive attitudes which reinforced their sense of isolation and distress.

Primal Wound

When asked what suggestions they have for counsellors, the majority of the participants said that counsellors need to understand the ‘primal wound’ and the profound and life-long effects of what happens to a baby when it loses its mother, something which is often not acknowledged in the context of adoption. Most viewed their premature maternal separation as the main cause of their distress well into adulthood, and believed that it also contributed to their physical health problems.

Two participants viewed the ‘primal wound’ as the foundation of their psychological lives. In contrast, two others did not find the deterministic aspect of the explanation helpful. To them, the ‘primal wound’ theory articulated the problem but then left them feeling stuck, defined by one event. Interestingly, some participants appeared to view the effects of the primal wound as changeable and not static. It helped them to make sense of the times in their lives that were emotionally intense. At other times, however, they distanced themselves from it and did not want it to define them. This conceptualisation gave them the ability to acknowledge that they were more than just their adoption experience, despite having periods in their lives where they had been through pervasive and painful emotions associated with their adoption.

Verrier (1993) holds that an understanding of the ‘primal wound’ is essential in working effectively with adoptees. This is a similar position to that taken by Dennis (2014), who suggests that a therapist may do more harm than good if they fail to understand preverbal implicit memory, and thereby dismiss the importance of an adoptee’s early life experience.

According to Lifton (1994), there are a number of factors associated with the practice of closed adoption that exacerbates the on-going effects of the original separation trauma. These include denial and secrecy, shame, growing up biologically disconnected and disempowered, the development of a false self in families where there is rejection of adoptive differences, and the process of reintegration. Lifton refers to this as ‘cumulative adoption trauma’, less deterministic than the ‘primal wound’ theory, and more in line with the experiences of the participants who felt that their early separation helped shape but not define them.

The study found that the extent to which the adopted person identified with their adoption depended on how affected they were at that particular stage in their life. The ‘primal wound’ may be a factor that predisposes adoptees to later distress, but which often seemed to require a significant event to trigger it, such as reunion, the birth of a child, or other losses. Perpetuating factors that delayed the resolution of these emotions related to disenfranchisement, such as further rejections from others in response to their attempts at grief resolution, or expressing their thoughts and feelings about adoption or reunion with their natural mothers. This means that the distressed person becomes isolated, and therefore, unable to accept and integrate the emerging emotions.

The supports and self-soothing skills that some people rely on for dealing with intense feelings and distress may be unavailable for adoptees who were never taught that it is acceptable to feel anything other than happiness about their adoption. Consequently, adoption may become even more significant in that person’s life narrative as associated conflict and avoidance arises within the self. It may take a lifetime to learn to ‘make room’ for their inner experience, and to cultivate the self-compassion necessary to successfully integrate hurt which has not been acceptable to others and therefore not acceptable to the adopted person either. It is possible that the ‘pushing out’ of emotions learned early on accounts for the pervasive or overwhelming emotional experiences encountered by adoptees in adulthood.

Disenfranchised grief

The participants’ accounts of the denial of their adoption-related feelings is consistent with Robinson’s (2004) observation that adoption grief is disenfranchised, ‘not openly acknowledged, publically mourned or socially supported’ (p. 5), an observation also made by Kenny et al. (2015). There are no rituals to help acknowledge and support the mourning process in adoption. Similarly, Kenny et al (2012) found that many of the adoptees in their study experienced denial of their grief by the counselling and medical professions.

Stages of emotional integration

Most of the participants in this study described moving from an early stage in their lives where they were disconnected from their feelings, to being overwhelmed with pervasive emotions in adulthood. Some experienced an increasing sense of loss as they grew up, aware that something was wrong, but not being overly affected. The most emotionally intense phase was usually in adulthood, when they had more fully integrated the meaning of their adoption, and often coincided with the search for their natural mothers, or a subsequent reunion.

For the majority of participants, their emotional response to their adoption changed over time, and this is consistent with the observations of Brodinsky et al. (1992) that feeling ‘lost’ and ‘abandoned’ and ‘found’ and ‘grateful’ can exist in the same individual at different stages in their lives.

Similarly, Dennis (2014) states that adoptees, as in all clients, present on a spectrum of awareness, from strong denial and unconsciousness, to highly attuned and aware. Furthermore, Penny, Borders, and Portnoy (2007) found that the stages of emotional integration occur gradually and change over time. A period of denial typically characterised childhood and various stages of deeper integration occurred from early or middle adulthood into late adulthood.

Pervasive emotions

Many participants described encountering intense, pervasive emotions such as grief, depression, and anxiety, including panic attacks. Some referred to this experience as a ‘breakdown’, ‘falling in a heap’, ‘trauma’, or ‘intense grief’, episodes that recurred over a period of many years and which at times greatly diminished their ability to function. These pervasive feelings were consistent with Moran’s (1993) observations of the intensity of post-reunion emotions. Kenny et al. (2012) found that 30% of their sample of adoptees met the criteria for a psychological disorder, but it is not clear whether this statistic corresponds to grieving, the effects of reunion, or to other factors. Brodinsky et al. (1992) explain: ‘We and many other clinicians have found a pattern in normal adoption adjustment: when adoption arises as a salient issue in a person’s inner life, the most pervasive feeling is an overwhelming sense of loss. The loss inherent in adoption is unlike other losses we have come to expect in a lifetime, such as death and divorce. Adoption loss is more pervasive, less socially recognised, and more profound’ (p. 9).

Robinson (2004), Lifton (1994), and Verrier (1993) were particularly concerned with the disenfranchised nature of this grief because it tends to intensify when it is not socially supported. For this reason, it is important that counsellors working with adopted adults are aware that intense grieving is normal, and that invalidation may not only contribute to the distress, but may also block the process of grieving and integration. A trauma informed approach as recommended by the APS (2015) would allow for grief reactions, essential if counsellors are to help their clients integrate their grief and loss.

Conclusion

A counsellor with a client who does not view their adoption as an important factor in their life might explore the climate of secrecy and fear of rejection their client may have experienced, including the types of supports that are available to them now. If the adoptee was rejected by others as a result of having questioned their adoption it may be a very difficult topic for them to discuss. At certain times in their lives, adoptees may not view adoption as important, and so it is essential that they be respected as the experts of their own life story. Counsellors should not collude with this dismissal of adoption, however, and might instead listen for themes related to identity, rejection, loss, abandonment, secrecy, and shame (Dennis, 2014). These can be addressed therapeutically with relevant, well-formed questions, without imposing specific interpretations on the client.

Counsellors need to be aware of the possible grief and trauma responses to adoption separation, and that these responses may be triggered by life stage events, such as reunion, the birth of a child, or other losses. They should also be aware that an additional layer of issues relevant to adoption may accompany an adoptee’s experiences of these life stages.

The majority of participants in this study felt that counsellors should understand that adoption is preceded by the lived experience of separation from their mother, and be able to recognise the on-going effects of this separation, as described by Verrier’s (1993) theory of the ‘primal wound.’ There were differences in the way the ‘primal wound’ was integrated into the participants’ narratives, with some finding the theory too deterministic, believing that their early separation experience had probably shaped them psychologically, but that it did not define their sense of self. A majority of the participants, however, regarded it as fundamental to understanding their emotional reactions to adoption separation and its lifelong impacts.

While the ‘primal wound’ is often dismissed as empirically unsupported, there is a growing body of evidence in relation to the long-term impacts of neonatal and preverbal early life experiences (Dennis, 2012; Kenny et al., 2015). Regardless of how such theories are evaluated, the counsellor should consider the adoptee to be the expert on their own life story, including what adoption means to them. It is not necessary to impose the ‘primal wound’ on those not ready to assimilate it, but by keeping it in mind as part of a trauma informed approach, the counsellor may be better placed to create a more therapeutic ‘psychological holding space.’ This will bring an attitude of acceptance of their client’s emotions and avoid responses that are based on outdated and unhelpful preconceptions.

Integrating adoption will most likely require skills that many adoptees have not previously learnt, such as self-soothing, distress tolerance, grounding, and emotional regulation, and so may be an important part of skill development during counselling. While the APS (2015) addresses psychological formulations for people who are adopted, this has been neglected in the overall psychological literature on adoption.

In the context of this study, case formulations include the predisposing factors, such as early separation and the absence of information about natural parents, and the precipitating factors, such as reunion, birth of a child, or other loss. They also include the perpetuating factors, such as reunion and the calibration of natural family relationships, adoptive family dynamics, denial, and stigma, and the protective factors, such as social support, adoption sensitive and trauma informed counselling, and coping skills.

Additional empirical research on these factors would be helpful in relation to informing counselling practice. Although Kenny et al. (2012), Kenny et al. (2015), and the APS (2015) make suggestions for services delivery, their target audience are clinicians working in mainstream health services, and there is limited research evidence on specific interventions.

Further research that explores individual counselling treatments for adults who were adopted is essential for building an evidence based approach to the treatment of adopted adults, and other parties affected by adoption.

Notes about Author

Sue is a practicing psychologist in Melbourne and works in a government funded community mental health and counselling service. In addition, Sue is in the process of starting her own private practice with a view to supporting adults affected by adoption. Sue has been a member of VANISH for 25 years.

For more information you can email Sue at piecepsychology@gmail.com

Sue was interviewed in 2016 by Ipsify editor, Thomas Graham, whilst conducting her research for her thesis. The interview was published in Ipsify in the same year.

References

Australian Psychology Society. (2015). Forced adoption practice guidance. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/forced-adoption/

Baden, A. & Wiley, M. (2007). Counselling Adopted Persons in Adulthood: Integrating Practice and Research. The Counselling Psychologist, 35(6), 868-901.

Brodinsky, D.M., Schechter, M.D., & Henig, R.M. (1992). Being adopted: The lifelong search for self. New York: Anchor Books.

Dennis, L. (2014). (Eds). Adoption Therapy Perspectives from Clients on Processing and Healing Post-Adoption Issues. Redondo Beach: Entourage Publishing.

Friedlander, M. (2003). Adoption: Misunderstood, Mythologized, Marginalized. The Counselling Psychologist, 31, 745.

Grand, M. (2010). The Adoption Constellation. San Bernardino, USA, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Green, S. (2014). Looking through the ‘lens of adoption’ in working with loss and trauma. Training Manual. Vanish Inc.

Kenny, P., Higgins, D., Soloff, C., & Sweid, R. (2012). Past adoption experiences. National

Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices. Australian Institute of family Studies. Research report no. 21.

Kenny, P., Higgins, D., & Morley, S. (2015). Good practice principles in providing services to those affected by forced adoption and family separation. Melbourne, Australia. Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Lifton, B.J. (1994). Journey of the adopted self. New York, Basic Books.

Moran, R.A. (1994). Stages of Emotion: An Adult Adoptee’s Post-Reunion Perspective. Journal of Child Welfare, 3, 249-259.

Penny, J.L., Borders, D., & Portnoy, F. (2007). Reconstruction of adoption issues: delineation of five phases among adult adoptees. Journal of Counselling and Development, 85, 30-42.

Robinson, E. (2000). Adoption and loss, the hidden grief. South Australia: Clova Publications

Verrier, N. (1993). The Primal Wound: Understanding the adopted child. Baltimore: Gateway Press.